Mostly, tonight is about telling the story of the Last Supper and the arrest of Jesus.

We celebrate Holy Communion as we tell the story of the night when Jesus first did.

This should remind us of just how much some of the story of Maundy Thursday – one key portion of it – offers language and gestures which are central to our faith all throughout the year.

Where would we be without it?

Just what would going to church entail?

We don’t quite know.

Of course, that makes it all the more important for us to put that part of the story more squarely back in context.

We want to be sure we’re telling it correctly and getting what it’s trying to teach us.

Tonight’s service is about receiving a fuller story, and a fuller message rather than trimming them down to suit.

When you do that, it becomes clear almost immediately that we need to think much more carefully about the place of grief in this story.

Because, actually, grief is the story.

The Last Supper – the founding of Holy Communion – is a practice of hope and connection that will only truly make sense once Jesus is taken from the disciples and from the world, which he’s about to be.

Jesus is the only one who knows, but knowing it is terrible and unspeakably lonely.

This shapes the whole evening.

As people reading the gospels later, we can see that.

This is most clear after the supper, when Jesus and the disciples go to pray in the Garden of Gethsemane.

Jesus wrestles with what lies just ahead and goes off a distance by himself to pray.

He asks God for some other way forward before it is too late.

He asks the others to stay nearby and to pray, too, although he does not tell them why.

As we see, his grief is almost overwhelming.

Then, after praying alone for a while, he goes back to where he left his friends, only to find them fast asleep: a horrible discovery.

It’s then that Jesus realizes just how truly alone he is.

It’s like someone standing at a payphone trying to call for help, calling every number they know, flipping through the little pages of the address books we all used to have in our pockets—remember those?—but nobody picks up.

Nobody’s home.

In the movie, “Dead Man Walking,” a nun, Sr. Helen Prejean, begins a ministry to death row inmates at Angola Prison and to families—both those of the inmates and those of their victims.

She offers herself as a spiritual advisor.

But what this will really mean only becomes clear when one of the inmates loses his final appeal, and it is time to help him prepare for his execution.

He is guilty of the crime, a fact that he admits only reluctantly, even to himself.

But eliciting this confession is not the point of Sister Helen’s ministry, even if it might provide a degree of consolation to some, and even the man himself.

Sister Helen’s real contribution turns out to be less abstract.

She learns that his family will not be there to witness the man’s execution.

And so she decides that she will be there.

She says: “I want the last face you see in this world to be a face of love. So you look at me while they do this thing. I’ll be the face of love for you.”

That points to what is so shocking about tonight’s story of Jesus in his grief.

Because in the midst of this ordeal, nobody has been prompted…moved…compelled to offer themselves as the face of love for Jesus.

Nobody has been looking carefully enough to notice his struggle.

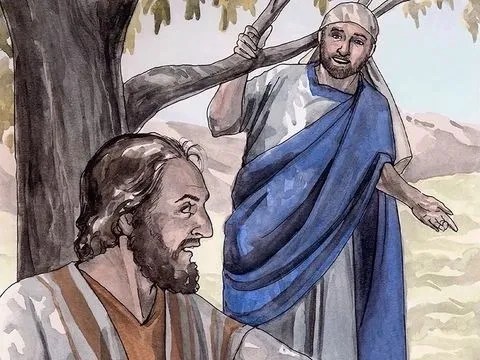

The only kiss that’s offered in the garden is a sign of betrayal.

Somewhere, I’ve read speculation that the arrest in the Garden would have been worse, and even more painful for Jesus than his crucifixion at Golgotha the next day.

There’s no way to know, of course.

However, it is true that the next day, when he dies on Friday afternoon, there would be faces of love distinct among the jeering crowd.

We know the disciples were there.

We know that Mary, Jesus’ mother and some of the other women were not just there, but actually closer to him than any of his other followers dared get.

He did not die alone.

But the night before, in the garden at his arrest, few had remained for very long.

By the time the Romans lead Jesus away, there’s nobody else standing there for them to arrest with him—there are no co-conspirators on hand for Judas to identify.

Jesus’ abandonment is complete.

We need to sit with that for a moment.

As we tell the story more fully, it’s important to pause to receive that grief. His grief.

And yet, something deeper is still at work.

Because wherever each disciple goes that night after they scatter, the next morning finds them gathered once again.

Sometime after dawn the next day, they’re back, standing among the crowds along the Via Dolorosa, and then even at cross itself…even if it means they might be next.

It’s a risk they’re now willing to take.

Something else inside them has taken hold.

It might be that they remembered the words Jesus had said at the meal – his promise that he will never abandon us, that he will forever be with us in our trials, and that all who find new life in him will be part of him and he of them.

After all, this is what Communion affirms.

That he will always be a face of love for us, and a source of strength as we seek to show the world a face of love.

It’s only as we step out into the dark night that we learn if this meal provides something that can actually sustain us, or if it’s just junk food.

Unless it equips us to offer the world a face of love, then we have missed its purpose.

And tonight, in coming together to hear the story in a fuller form, that’s what we practice.

We’re here to offer faces of love to Jesus as his final hours begin.

May it teach us to love the world as he did, and for his sake.

Amen.