For a while this month, I was following a discussion on BlueSky by a group of philosophers.

They were arguing about Christmas movies.

Now, philosophy may not be your thing.

Even if it’s not, it probably won’t surprise you to learn that professional philosophers really enjoy arguing.

So, someone decided to have at it on the subject of Christmas movies.

And one thing that came up has stayed with me:

When we call something a “Christmas movie,” are we talking about a movie that happens to occur at Christmas-time, or does Christmas make a difference in a specific way?

It’s a good question.

Predictably, there was much discussion about whether the 80’s action movie, “Die Hard,” should properly be considered a Christmas movie.

This went on until someone pointed out that “Die Hard” is about a small band of resistance fighters defending a tower against an overwhelming band of corrupt, foreign invaders.

And when you put it that way, it’s actually a Hannukah movie.

Make of that what you will.

Still, if you think about it, a Christmas backdrop doesn’t require much.

Backdrops rarely do.

A palm tree, a sporty convertible, and a few people in shades will signal that a story is happening in L.A.

A palm tree, a pastel building, and a guy in shades driving a cigarette boat will signal that a story is happening in Miami.

New York is all about taxicabs, hotdog stands, and somebody snarling that you should watch where you’re going.

Similarly, Christmas as a backdrop also has its own shorthand.

For sure: a string of twinkle lights, a Santa hat, and a ringing bell.

Often enough: an old red truck driving by with a fresh green tree, someone drinking cocoa, people wearing scarves in an I-don’t-really-mean-it sort of way.

Any of that and you know: we’re talking about Christmas.

By contrast, it’s something very different when Christmas is at the heart of the story, acting as the catalyst for someone’s wrestling and change.

The angel is in the details – the specifics of giving up and claiming; of stumbling, falling and rising up again; of listening to love and not someone else’s expectations – and this because of the language of the carols, the mystery of the candles, the vision of the prayers, the arrival of the child offer someone hope and a way forward.

There’s a difference between simply existing and truly living.

When you see it, as Christmas hopes we all will, there really isn’t a shorthand for it.

It’s at Christmas when the church comes closest to saying so outright, because when someone discovers the Christ child for themselves, they always do it in their own way, after their own journey.

The church knows that there’s no predicting what will prove to be a shelter for any of us, any more than we might say, in theory, what will lift our hearts in gratitude or what we might love so deeply that such love would drop us to our knees.

Wherever that is and whatever that looks like for us is where we find Christmas for ourselves.

Who that frees us to become is the start of a new life in God.

That’s why the worst way to tell a Christmas story is to let it be predictable.

To the church, however it is we get there, each experience of true encounter, reveals something new about God and gives new insight into what life might look like when it is lived as God’s gift.

This is what we celebrate at Christmas.

This is what we discover in Jesus.

One of the great early thinkers of the church, Athanasius of Alexandria, once observed that “God became man so that man might become God.”[1]

But again, this doesn’t mean losing ourselves or getting subsumed by the glory of it all.

It means that God gets so close to us so that we might – finally – get close to God.

It means finding our true selves: the person that you and only you could ever be, equipped to do the good that you and only you could ever do, as God intended.

Christmas says that anything else is less than it should be.

Now, we may well know a thing about that, too.

If you think about it, the backdrop for the Bible’s stories of Christmas is all about the weariness of the world.

There is this pervasive sense of hopelessness about ever getting out from under.

Under what?

Unfairness, selfishness, literal and perhaps spiritual poverty, judgment, ignorance: it’s a familiar enough list for us, too.

But then predictability goes out the window.

Because it’s in the midst of that weariness that angels come and a star appears, bringing tidings of how the slow and steady grind of life will not have the final word.

Some go out to meet the new world this opens up.

So many of Scripture’s own Christmas stories are wrapped up in accounts of various journeys and how they open up new worlds.

Joseph and Mary and the donkey to Bethlehem.

The magi meeting on the road, after each had set out from their own corner of world to follow the star.

The shepherds, who were nomads of a kind, out there on a largely continuous journey with their flocks, who divert to the manger under the direction of the angel.

Suddenly, something wells up from deep within them that tells them not to settle, not play it safe, not to put limits on what God can do.

Don’t just exist, it says.

Truly live.

Whatever that may entail.

Whatever that may look like as God’s particular gift to you.

However that might become your contribution to the world.

And it was kneeling in the manger that it truly dawns on each of them.

It’s then they understand that God’s love is beyond predicting.

It’s then they realize that God’s own son has come so that we might live as those who know, and so we might learn to go forth unafraid, in all our glorious complexity.

Just as it was for them, whenever we realize this now, it is Christmas.

The child is born, and we are reborn.

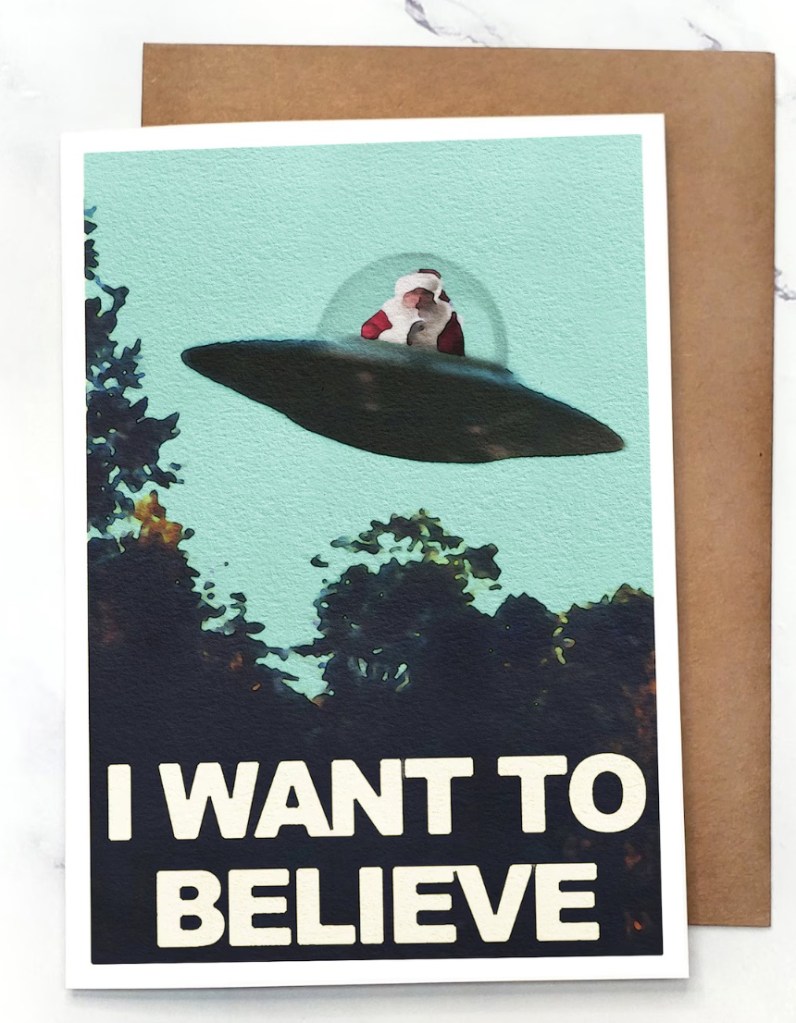

With that in mind, it seems fair to ask what kind of Christmas movie we might be in.

Tonight, we might ask ourselves just what we’ve been up to for the last few weeks – and maybe even what we’re up to this evening.

To what extent does Christmas come into how we spend Christmastime?

The stories themselves attest that God is not content to remain in the backdrop for very long.

They tell us that God loves us far too eagerly.

Most of all, they teach us to hope that it may be so.

Merry Christmas.

[1] “On the Incarnation” (54:3)