If you think about it, the Gospels don’t tell us nearly as much about the disciples as they seem to.

They’re sort of like an ice cream store with twelve different kinds of vanilla – well, eleven, anyway.

The most important thing about them is that they come to believe.

The second most important thing is that they eventually come to embody the Church, quite literally.

Their bodies are the first ones there.

Of course, earlier, they had been the first followers of Jesus, and again: this is literally true. They literally follow him.

But in story after story, it’s clear that they themselves don’t understand a lot of what they’re witnessing.

For miracle after miracle, healing after healing, feeding after feeding, even exorcism after exorcism, they have front row seats.

They know it matters to be there and don’t want to be anywhere else.

They get that this matters, even if they’re not sure how.

What the gospels never much try explain is how any of it matters to them, personally, or the difference that it makes, although there are a few exceptions.

After some spectacular cowardice, Peter will become much braver.

After some spectacular skepticism, Thomas will become far more certain about the resurrection.

All along, the women prove far more grounded, and yet, in loving Jesus, they are particularly emboldened, steeled to remain with him in his dying and to tend to his body after his death, even at great risk.

But aside from that, Scripture never tells us about more specific changes—how being with Jesus made James more forgiving, or Matthew more generous, or Philip more patient.

In a strange way, for them, joining Jesus both changes everything and, well, nothing in particular.

At least: nothing someone would go on to record for posterity.

Our Scripture this morning is, of course, recorded for posterity.

But it is striking that, here, too, to be with Jesus on the mountaintop both changes everything and, well, nothing in particular.

So, in the “changes everything” column, we have the appearance of Elijah and Moses, the uncloaking of Jesus in a “flashing, lightning white” (Ruden), the voice of God coming out of a cloud.

In the “nothing particularly changes” column, we have the disciples’ fear and astonishment.

Matthew and Mark’s versions of the story include Jesus explicitly telling Peter, James and John not to tell what they have seen, which is a detail Luke does not even bother to mention because, well, of course they won’t.

And this is where he’s telling us something very important.

Because what will keep this secret safe?

It isn’t safe because they’re quiet.

It’s safe because even now, with all they’ve seen, they are not yet truly changed.

There’s nothing really different about them…some way in which can’t help but radiate what they now know, even if they make sure not to breathe a word of it.

Faith isn’t who we are, or what we have, even in the wake of the most dazzling revelation.

It’s in what we learn, “however slowly, partially, imperfectly” as we find some freedom from the worship of anything less than God.[1]

And it is relentlessly specific.

We see it in the adult children who learn to become more patient with their aging parents, or the perfectionist who learns to become more patient with herself.

We see it as we learn a version of forgiveness that is not just some version of pretending to forget, but about discerning the ways in which renewed relationship might yet be possible.

We see it as we learn to give less attention to superficial concerns, and superficial people, and more to what’s deeper and to the people who are ready to go there with us.

These are not new commitments that life particularly demands us to declare out loud—that’s not the point.

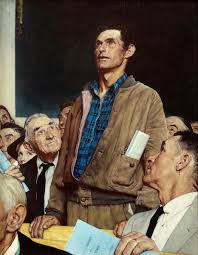

The point is that we know when someone is living in a new way – when the prevailing wind inside them has shifted, somehow, and they’re intent on a new course.

Because you cannot keep the secret of a changed heart.

You cannot keep the secret of a changed mind.

You cannot keep the secret of a life that has finally been changed by Jesus.

By contrast, even to be a disciple is not that hard, relatively speaking.

Front row tickets to the miracles might not be as hard to come by as we might think.

We might even hear the voice of God on a mountaintop.

But to be changed, however slowly, partially, or imperfectly, may be far more basic and even more astonishing.

Our Scripture this morning offers a final story of epiphany, concluding a season that began with the magi following the star to Bethlehem, and which now ends, all these weeks later, with this story of Jesus’ transfiguration.

But it leaves us consider how he might be calling us to new life in him, radiant in our generosity, dazzling in our kindness, and wondrous in our capacity to give and to love.

May any such life turn out to be the worst kept secret in the world.

Amen.

[1] See Nicholas Lash, Believing Three Ways in One God: A Reading of the Apostles’ Creed, 21.