This morning’s Scripture describes an early moment in the church when the Apostle Paul responds to a dire situation, doing so with creativity and love.

It’s amazing on a lot of levels, but just for starters, I mean it when I say things were dire: the setting is a Roman territorial prison; Paul and his assistant, Silas have been arrested, tried, nearly killed by a mob and badly beaten; then in the middle of the night, there’s a massive earthquake.

But it turns out to be a funny sort of earthquake.

It’s an earthquake that shakes the foundations of the prison, opens the door of each and every cell, and, as it just so happens, also undoes all of the restraints on each and every prisoner.

That’s the full extent of the damage.

So maybe it’s not so dire, after all, right?

Most of the city probably slept right through it.

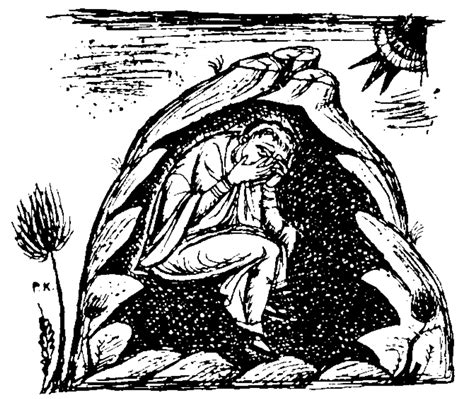

But for one person, it’s a complete catastrophe.

That person is the jailer.

Because the jailer wakes up, sees what has happened, and immediately pulls out his sword, figuring on ending his own life right then and there.

This impulse says a lot, actually.

What it suggests is that, by his reckoning, suicide is bound to be less awful than whatever punishment his Roman employers will be sure to cook up when they find out.

Back then, when things fell apart, Rome often looked for ways to make an example of you.

So when it came to a jailer who lost a prison-full of people in the middle of the night after an “earthquake,” it didn’t seem likely that Rome would understand.

Of course, if you’re Paul or Silas, you actually have a pretty good idea of what had happened.

God was at work.

But this is where love and creativity come in.

Because instead of giving each other a high-five and heading off into the night, as they might have done, Paul and Silas stay right where they are.

What’s more, they convince all the other prisoners to stay right where they are, too.

They could have run, but instead, they choose to stay.

Nobody says that they’re supposed to save the jailer.

But Paul and Silas make the choice to respond to this whole sequence of events in a new and unexpected way, and to try loving their enemy and seeing what might happen.

They try caring when they have every reason not to.

It isn’t a grand scheme. It’s just God.

II.

And this is what I want to think about this morning.

Because I read that and I can’t help but think: this is the church that speaks so powerfully to me: the church that stretches to make choices like that.

So much of the church at its best is to be found when it tries to look beyond our ugly rivalries and sees new possibilities.

It’s the church as we see it in moments like Paul and Silas in Philippi.

It isn’t always like that, of course.

But let us not forget that there are also moments when the church comes back to itself, hears its own Scriptures anew, feels once again the transforming presence of the Spirit, and sees its work (remembers its work?) with fresh perspective and commitment.

There are moments when we stretch.

Those moments give us a way to imagine something beyond the same old game—and when they do, it can be amazing to see just how eagerly people step off the merry go round…how grateful they are to step back onto solid ground…more generous and peaceful ground…the kind of world God intended.

In this morning’s gospel, that’s just what the jailer does.

Acts tells us that he spends the rest of the night bandaging Paul and Silas’ wounds, giving them something to eat, and starting a whole new life right then and there, no longer bound by the rules of the same old game – the very rules it has been his job to enforce.

He and his whole family become Christians right there under Rome’s nose.

And maybe they pack up and go do something else…or maybe they just stay and find ways to be Christian in that context.

Either way, this is Scripture’s first signal that Rome itself will come to be transformed by the love and creativity of God’s people.

III.

And I have to say, I’m kind of feeling this right now.

I’m ready for the world to be transformed like that again.

I’m ready to be transformed that way, myself.

I’m hardly one to sing about disruption – to me, most of the time that’s just opening a Pandora’s box.

But I would be thrilled to see the foundations of our old divisions shaken, and what feels like the same old game get disrupted as people reach for something better…as we decide to step off the merry-go round.

Because I know how earnestly I long.

I long for a world that’s better than this one sometimes seems as if it even wants to be.

I long for a world where people can disagree and still keep talking.

I long for a world where we don’t pretend that all the answers are simple, but where there are also space and grace to figure things out, to not be there yet, to be learning, to have questions, to be stretching.

It’s something I can scarcely describe and cannot locate, but that my heart knows better than the scent of my mother’s perfume.

You may disagree with me about plenty, but I bet you know exactly how that feels.

Paul and Silas have come to tell us that it may not be nearly as mysterious and elusive as we think.

Because as we let God into our lives and let ourselves be drawn into God’s own life, things happen.

People change.

We recognize the choices, not that we have to make, but that we get to make between the world as it is and as it might be.

We get our own invitation to live with love and creativity in this moment and make a church that sees beyond one agenda or another, but says everyone needs saving, somehow.

The church is how God embodies the idea that we have it in us to be a force for good, not in some simplistic sense of making everybody Christian – that’s thinking too small – but in the sense of being called to reject any agenda that tries to keep people apart for its own purposes, and to live deeply and joyfully in a very different way.

This is what I want church to be about now.

This is the work I would love to see us get back to.

In its muddled and most distracted moments, the church can find itself playing the jailer in this story—enforcing someone else’s rules, desperately in need of the very things its gospels try to talk about.

In its greatest moments, the church shows the whole world how to take one big, collective step off the merry go round and back onto solid terrain.

And the world needs us to do that again.

The world needs people with this inexplicable call to love even when they have every reason not to…people who see their own cell doors fall open and decide not to leave, but to love right then and there.

May such people shake the foundations of everything that seems so broken right now, and teach the world to put its swords away, and come live.

Amen.