I know I’ve told you before about my year doing temp work in downtown Philadelphia.

My energy for school had conked out rather unexpectedly just before the start of a new school year, which meant that when September arrived, I turned out not to have any particular plans.

That was just one way in which my act was (how should I put it?) not together.

But the moment I am remembering today happened later on; in fact, it was just about now, in mid-March, in this stretch of weeks when any given day might be spring, might be winter, but even so, there are no leaves, there are no birds.

There are only the wind and the various exhausted shades of brown wherever you might happen to look.

My job – as I have mentioned before – was sort of perfect for the season.

I was filing tax returns for dead people.

If you don’t know, you still owe taxes for whatever part of the year that you’re alive.

But filing any time after that turns out to be tricky for most people.

So, there are people who help with that.

My particular piece of it was pretty simple.

I had a red ink pad and a big, old school librarian sort of stamp, and my job was to stamp the words FINAL RETURN on the front page and then get it ready to be mailed out.

This sounds easy enough, and it was.

Except now is when I mention that I was working for Fidelity Investments.

Any Fidelity customers here?

So…multiply yourselves by ten zillion, and you can begin to imagine just how many returns needed to be stamped and prepped in the weeks before Tax Day.

You almost needed a ladder to get to the top of the pile.

You could measure your daily productivity literally in how many feet of final returns you’d been able to get done.

But every day, at noon and five, one of the accountants would wheel this little hand truck over with another four feet or so of returns to add to the bottom of the pile.

Do you remember that scene where Lucy and Ethel are working on the assembly line with the chocolates?

Or that movie where Charlie Chaplin gets sucked into the gears of the machine?

It was like that. Every day. For nearly three months.

And so, ever since, nary does a St. Patrick’s Day pass for me without the distinct memory of that particular year, with its tug of war between winter and spring, and the feeling that I was running as fast as I could, desperately trying to go up the down escalator, knowing that whatever I did, the one thing I could not do was stop.

And yet: where was I actually going?

There was no clear answer to that question.

Have you ever felt that way?

It’s bad, right?

At another point in that same general span of years, there were three days when I literally didn’t have money to eat, and yet I was too embarrassed to ask someone for a loan (which was ridiculous).

That was bad.

Even so, I can say without any hesitation whatsoever that my time filing tax returns for dead people was worse.

And I think this is something that Jesus really understood.

It wasn’t the job.

Actually, there was nothing wrong with that job, per se.

At a different season of my life, with a slightly different configuration of coworkers, a dog waiting for me when I got home, or a bigger project in my off-hours that I got to be a part of, and the job itself would have been weird, but fine.

So much that is not great in itself can be fine, provided, of course, that we ourselves are mostly fine.

But what does it take, even just to be mostly fine?

This is a Jesus kind of question.

And it’s why I think he has such compassion for us when we’re stuck and can’t seem to answer it – to find whatever our answer might be, no matter how hard we try.

With him, it didn’t matter if you were rich or poor, healthy or sick, Jew or gentile – he could tell when that particular poverty of spirit was wrapped around you, like a boa constrictor.

In the face of just that, he affirmed that God wanted something very different for his children.

…Which (take it from me), when you’re in that situation, is almost the hardest thing you can be asked to believe…

And yet this is the leap of faith Jesus wants to help us make.

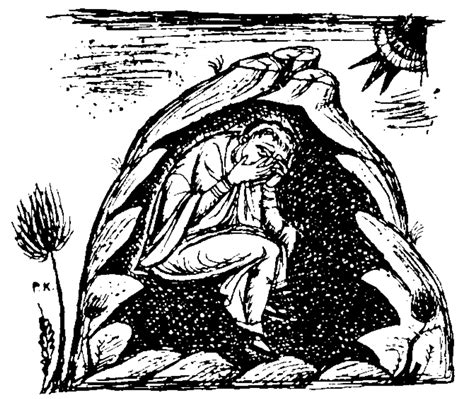

In situating the passage before the reading, we mentioned the “noonday demon,” a phrase that we have, courtesy of St. Jerome’s translation of the Bible into Latin.

As demons went, it was considered one of the most active, with a particular capacity to drain our lives of purpose, delight, or direction, and to leave us perpetually feeling like the brown landscapes of March, always somehow caught out in a biting, cold wind.

Unlike the other demons, who lured you in by offering some form pleasure that was great until it finally went bad, the noonday demon convinced you just to sit tight in a state of vaguely miserable exhaustion, more or less forever.

This was a vital discovery.

The noonday demon gives the church a way to recognize that apathy and hopelessness are, in fact, forms of sin—ways of denying the goodness and purpose of God in the world.

By contrast, apathy and hopelessness offer excuses for not bothering to do more with our lives, and (whatever form that “doing more” may take) to find life and joy in doing it.

The belief that any single life cannot make a difference to someone, somewhere may be the most sinful one of all, egregiously wasting God’s gifts of life and love in exchange for a parade of one quivering anxiety after another.

As John Ruskin once observed, “When a man is wrapped up in himself, he makes a pretty small package.”

But with Jesus, there is God’s ongoing invitation to offer the gift of oneself, and to be opened, just as Jesus offers himself and is opened by a world in such desperate need of his love.

Speaking hopefully of any of us, the Psalmist writes:

“Because he[b] loves me,” says the Lord, “I will rescue him;

I will protect him, for he acknowledges my name.

15 He will call on me, and I will answer him;

I will be with him in trouble,

I will deliver him and honor him.

16 With long life I will satisfy him

and show him my salvation.” (Psalm 91:14-16)

In the living of our days, the only return that finally matters is when our hearts return to God, and our days break forth into blossom.

Amen.